Creating a Food Forest: Best Drought-Tolerant Fruit Trees and Shrubs

- Herman Kraut

- Jul 10, 2025

- 8 min read

When Half Your Trees Die, You Learn Fast

I didn’t set out to lose half my food forest in the first year. But I did.

I had the books, the diagrams, the 10x10 meter grid, and the Tree Trio dream—fruit, nut, nitrogen fixer—planted like clockwork. But nature had her own layout: frost pockets, dry spells, elevation quirks, and relentless sun. I learned quickly that drought-tolerant fruit trees don’t mean carefree planting, and food forests don’t build themselves.

That loss taught me to slow down, observe, and adapt my design to real conditions. Now, with a more focused approach, denser planting, and smarter tree guilds, our forest is finally starting to take shape.

This post is part of our Drought-Tolerant Plant Series — check out our guide on herbs that survive dry spells and medicinal herbs for hot climates to build resilience from roots to canopy.

Let’s dig in, layer by layer.

Designing a Food Forest for Dryland Resilience

A food forest, in permaculture, is more than just an orchard. It’s a layered, self-sustaining ecosystem modeled after a natural forest, designed to produce food, fuel, medicine, and soil fertility with minimal human input over time. Unlike annual gardens that need regular tending, a well-planned food forest becomes more productive and low-maintenance as it matures.

But here’s the catch: most food forest designs are based on temperate or tropical climates. If you’re working in a Mediterranean climate, with long dry summers and sporadic rainfall, the approach needs to shift. Shade, microclimates, and water efficiency become your top design priorities, not lush growth from day one.

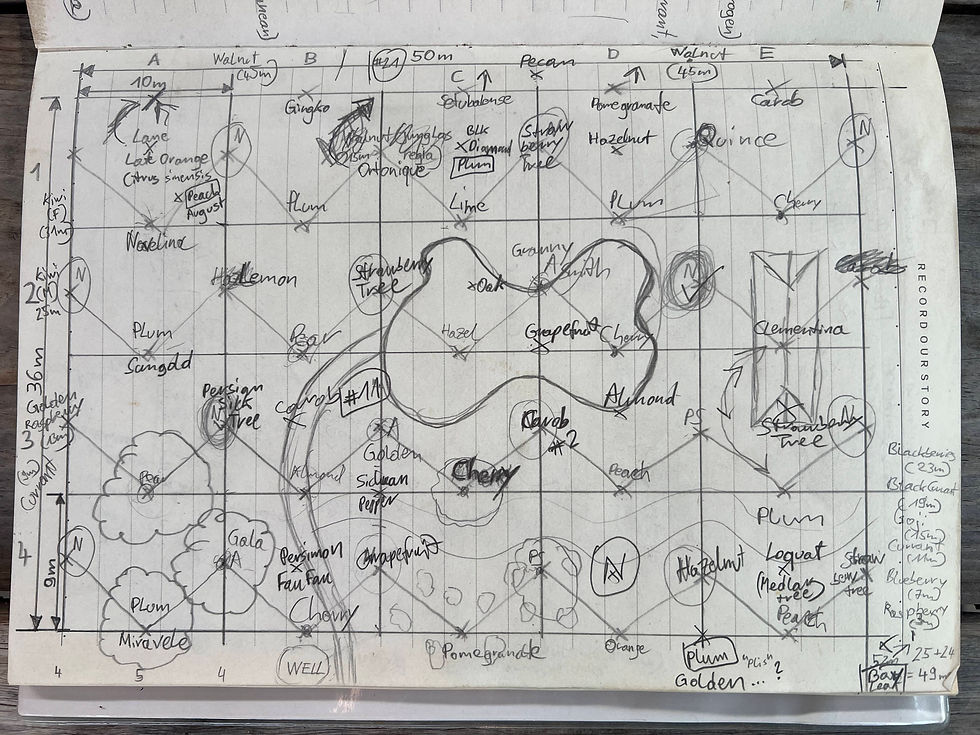

When we moved to our land in Central Portugal, designing our food forest was one of my top priorities. I chose the flattest, most accessible part of our property near the stream that marks our southern border. After consuming countless permaculture books and videos—including Stefan Sobkowiak’s Tree Trio method—I mapped out a 10x10 meter grid, like a true German engineer.

The idea was simple: plant groups of three trees in triangular patterns—one fruit, one nut, and one nitrogen fixer. Repeat across the grid for function and diversity. But nature had her own grid overlay: frost pockets, soil inconsistency, and sun exposure differences all conspired to teach me one key lesson...Observation beats ambition.

Roughly half the trees we planted in that first year died. That failure became our guide. In Year Two, I narrowed my focus to a south-east facing zone, easier to water and protect. I added sun-shielding grasses around the eastern and southern sides of young trunks. I shifted from rows to guilds. I planted tighter and smarter, not wider and wilder.

The truth is, a food forest in a dryland climate evolves over years. Some species thrive, some fail, some surprise you. The layers aren’t static. They respond to your land, and your role is to listen, test, and adapt.

Layering Strategies for Dryland Food Forests

In theory, a food forest is a lush, multi-layered ecosystem—seven vertical zones of abundance dancing in harmony. In practice? My first attempt looked more like a stubborn orchard on life support.

That’s when I started observing what really wanted to grow where. The magic of permaculture layering isn’t just about stacking plant heights. It’s about stacking functions, adapting to microclimates, and planting in sequences, not perfection.

Let’s look at the classic seven plant-based layers of a food forest—plus the often-overlooked 8th layer: the human layer. As steward, observer, harvester, and designer, your role is the thread that ties it all together, especially in dry, Mediterranean-style systems where every plant’s success depends on thoughtful placement and ongoing observation.

1. Canopy Layer

Trees: Carob, Olive, Jujube

Functions: Shade, windbreak, water retention

2. Understory Layer

Trees: Fig, Pomegranate, Loquat

Functions: Edible, semi-shade-tolerant, early fruiting

3. Shrub Layer

Plants: Feijoa, Autumn Olive, Santolina

Functions: Wind protection, pollinator support, nitrogen fixing

4. Herbaceous Layer

Plants: Comfrey, Yarrow, Chicory

Functions: Mulch, mineral accumulation, weed suppression

5. Groundcover Layer

Plants: Oregano, Thyme, Strawberries

Functions: Living mulch, weed control, erosion protection

6. Climber Layer

Plants: Grapes, Passionfruit (sheltered), Malabar spinach

Functions: Shade, vertical productivity, space efficiency

7. Root/Soil Layer

Plants: Daikon, Dandelion, Fennel

Functions: Soil structure, fungal networks, nutrient cycling

8. The Human Layer

You’re the most important layer of all. Your choices shape the system. Your observations steer the evolution. In drylands, where every drop of water and every square meter counts, being present, patient, and responsive is what makes a food forest thrive.

Tough Tip: Walk your land often. Notice where dew collects, where shade falls, where plants struggle. Let your decisions grow from that, not from someone else’s climate or diagram.

Companion Planting and Tree Guilds That Work

In dry climates, tree guilds are your food forest’s defense team. Instead of planting in isolation, each fruit or nut tree is surrounded by allies.

Guild Example – Fig Tree Guild

Main tree: Fig

Nitrogen fixer: Autumn Olive

Dynamic accumulator: Comfrey

Living mulch: Thyme

Pest deterrent: Garlic chives

Bonus: Use tall grasses like vetiver and lemon grass or sacrificial shrubs to shade the base of young trees, especially on the south and east.

Tough Tip: Start simple. One tree + 2–3 helpers is more manageable than a dozen mismatched plants.

Water-Wise Orchard Design in Real Life

Dryland food forests are built with the water budget in mind.

What Worked for Us:

South-east orientation for morning sun and reduced afternoon stress

Zone-first approach: one manageable area instead of wide planting

Mulch pits and swales to direct rainfall

Graywater reuse for tough spots

Tough Tip: Even on small land, microclimates matter. Know your frost pockets, slopes, and sun traps before planting.

Top Drought-Tolerant Fruit Trees and Shrubs

These fruit and nut trees aren’t just tough, they’re proven performers in Mediterranean and dryland climates. Each species below is easy to integrate into food forest guilds and offers multiple functions like food, shade, or pollinator support.

Olive (Olea europaea)

A classic for drylands. Olive trees thrive in poor soil, need little water once established, and live for generations. They double as windbreaks and evergreen canopy.

Best for: Sunny slopes, rocky soil, long-term canopy

Tough Tip: Don’t overwater young trees. They thrive on stress—not pampering.

Carob (Ceratonia siliqua)

A deep-rooted, drought-loving tree that offers shade, soil stabilization, and edible pods. It grows slowly but pays off in long-term resilience.

Best for: Dry, exposed zones or erosion-prone slopes

Tough Tip: Pair with a nitrogen fixer or fast-growing pioneer to protect it early on.

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata)

A hardy nitrogen fixer that improves soil fertility and produces tart, antioxidant-rich berries. It grows fast and can tolerate heat, drought, and wind.

Best for: Tree guilds, food forest edges, quick cover

Fig (Ficus carica)

Fast-growing, deeply rooted, and incredibly forgiving. Figs offer generous yields even with minimal care. They thrive in sun and tolerate dry spells.

Best for: Early yields, light canopy, fast food production

Tough Tip: Cuttings root easily—propagate from your best performer.

Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

A tough, deciduous shrub or small tree that produces nutrient-rich fruit and tolerates intense sun, wind, and low water.

Best for: Harsh zones, privacy screens, edible hedging

Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica)

An evergreen tree that tolerates drought better than it looks. Produces fruit early in the season and holds moisture well once established.

Best for: Sheltered spots, graywater systems, shade transition zones

Grape (Vitis vinifera)

A vigorous vine that provides shade, fruit, and vertical yield with smart pruning. Loves dry heat once established.

Best for: Trellises, fences, arbors, shade tunnels

Tough Tip: Prune hard every winter—grapes fruit on new wood.

Feijoa (Acca sellowiana / Pineapple Guava)

A dense evergreen shrub with edible flowers and fruit. Feijoa works well as a windbreak or mid-layer tree guild companion.

Best for: Guilds, low-maintenance fruit, structure and privacy

Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba)

One of the toughest fruit trees around. Jujube tolerates poor soil, extreme heat, and total neglect—but still delivers nutritious fruit.

Best for: Dry zones, wildlife edges, low-effort orchards.

Tough Tip: Protect young trees from frost and strong wind in the first year.

Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo)

A Mediterranean native that offers year-round interest and food. Its berries are edible (though best in jam), and its flowers attract pollinators.

Best for: Borders, pollinator zones, fire-resilient hedgesTough Tip: Needs almost no maintenance—plant it and enjoy.

Designing a food forest in a dry climate isn't about copying diagrams from a textbook. It’s about reading your land, experimenting boldly, and adjusting when things don’t go as planned.

Start with one manageable zone. Layer your plants with intention. Choose drought-tolerant trees that earn their water, and guild them like a family that’s got each other’s backs.

Join the Kraut Crew to see how our food forest evolves—one tree, one guild, one lesson at a time.

Herman’s Tough Kraut Fixes: Common Challenges with Drought-Tolerant Fruit Trees and Shrubs

Growing a thriving food forest in a dry climate is a long game, especially when working with drought-tolerant fruit trees and shrubs. While these resilient species are built to survive with minimal water, they’re not immune to failure—especially in the first few years. From sun-scorched trunks and slow growth to surprising frost damage and poor soil performance, we’ve faced our fair share of setbacks here on the homestead.

This section dives into the most common mistakes and troubleshooting tips for establishing drought-tolerant fruit trees in a Mediterranean or dryland climate.

Q: My drought-tolerant tree still died. What went wrong?

A: Even tough trees need the right start. Young trunks can scorch in full sun or struggle in poor soil. Shade the base with tall grass or mulch, water deeply (not often), and avoid planting in compacted or windy spots.

Q: Do I really need to water these trees if they’re drought-tolerant?

A: Yes, especially in the first 1–2 years. Deep, infrequent watering trains roots to grow down. Once they’re established, most species can survive on rainfall, but early neglect usually leads to failure.

Q: What’s the easiest way to design my food forest layout?

A: Start small. Pick one sunny, sheltered zone (ideally southeast-facing), plant a few tree guilds close together, and build out yearly. Don’t spread too thin too fast—tight zones are easier to water and manage.

Q: Can I plant all seven layers at once?

A: You can, but you probably shouldn’t. Start with a tree and 2–3 support plants. Add layers as you observe what works. Some plants will die. That’s normal. Build guilds slowly and adapt as the canopy grows.

Q: Why are my fruit trees wilting even though it’s not that hot?

A: Could be wind stress or shallow roots. Young trees need protection on the windward side. If the soil is dry only at the top, your roots may be staying too close to the surface. Mulch deeper and water slowly to push roots down.

Recommended Reads for Your Dryland Food Forest

Building a food forest, especially in a dry or Mediterranean-style climate, is a journey of observation, experimentation, and layered design. These books have earned their place on my shelf, and I reach for them often when planning new zones, choosing species, or rethinking my strategy after a failed planting.

Each one delivers practical knowledge you can apply right away. No fluff, no filler.

By Dave Jacke & Eric Toensmeier

If you want to go deep into the ecology, science, and strategy of forest gardening, this is the foundational text. Volume 1 explains the “why” behind food forests, while Volume 2 dives into site design, plant selection, and real-world application. It’s dense but worth every page.

By Darrell Frey & Michelle Czolba

This one is perfect for small-scale homesteaders. It breaks down the food forest process into manageable chunks—from choosing drought-hardy trees and shrubs to building soil and long-term care. Easy to read, visually friendly, and highly practical. Great for anyone working on under 1 hectare or designing in steps over several seasons.

By Mark Shepard

Ideal if you're thinking beyond the garden and toward land regeneration on a broader scale. Shepard explains how tree crops, silvopasture, and perennial systems can restore degraded land and build long-term resilience—especially in dryland settings. This book is not just for farmers, many of the insights apply to off-grid homesteaders, too.

Comments